List of captured German and Romanian military leaders. Field Marshal Paulus and German generals in Soviet captivity

On January 30, 1943, Hitler promoted Friedrich Paulus, commander of the German 6th Army that fought at Stalingrad, to the highest military rank - field marshal. The radiogram sent by Hitler to Paulus, among other things, said that “not a single German field marshal has ever been captured,” and the very next day Paulus surrendered. We bring to your attention the diary report of the detective officer of the counterintelligence department of the special department of the NKVD of the Don Front, senior lieutenant of state security E.A. Tarabrin about finding and communicating with German generals captured at Stalingrad.

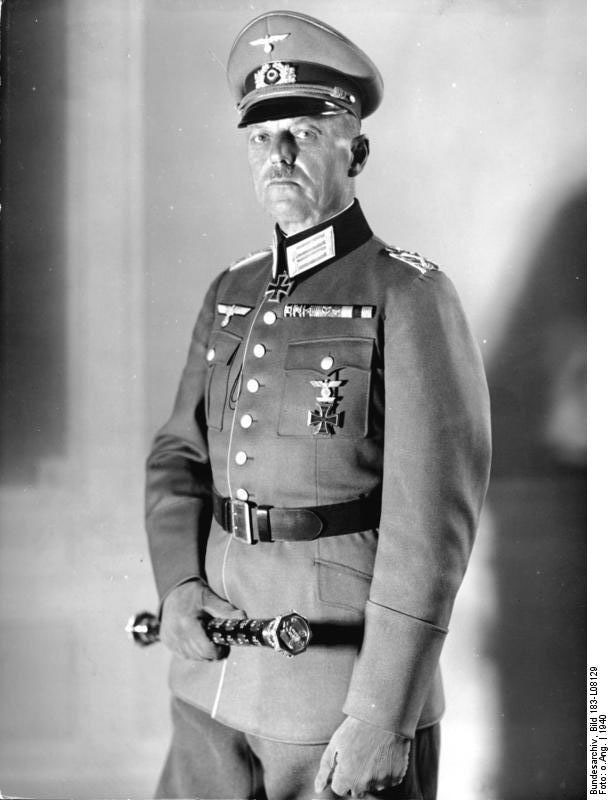

Field Marshal Friedrich Wilhelm Ernst Paulus, commander of the 6th Wehrmacht Army encircled in Stalingrad, chief of staff Lieutenant General Arthur Schmidt and adjutant Colonel Wilhelm Adam at Stalingrad after the surrender. Time taken: 01/31/1943,

Diary-report of the detective officer of the counterintelligence department of the special department of the NKVD of the Don Front, senior lieutenant of state security E.A. Tarabrina 1 about finding and communicating with the generals of the German army who were captured by the troops of the 64th Army in Stalingrad

Received orders to be placed with German general prisoners of war. Do not show knowledge of German.

At 21:20, as a representative of the front headquarters, he arrived at his destination - to one of the huts in the village. Zavarygino.

In addition to me, there is security - sentries on the street, Art. Lieutenant Levonenko - from the headquarters commandant's office and the detective officer of our 7th department Nesterov 2.

“Will there be dinner?” - was the first phrase I heard in German when I entered the house in which the commander of the 6th German Army, General Field Marshal Paulus, his chief of staff, Lieutenant General Schmidt 3, and his adjutant, Colonel, were housed on January 31, 1943 Adam 4.

Paulus is tall, approximately 190 cm, thin, with sunken cheeks, a humped nose and thin lips. His left eye twitches all the time.

The commandant of the headquarters, Colonel Yakimovich, who arrived with me, through the translator of the intelligence department, Bezymensky 5, politely invited them to give them the pocket knives, razor and other cutting objects they had.

Without saying a word, Paulus calmly took two penknives from his pocket and placed them on the table.

The translator looked expectantly at Schmidt. At first he turned pale, then the color came to his face, he took a small white penknife out of his pocket, threw it on the table and immediately began shouting in a shrill, unpleasant voice: “Don’t you think that we are ordinary soldiers? There is a field marshal in front of you, he demands a different attitude. Ugliness! We were given other conditions; we are here guests of Colonel General Rokossovsky 6 and Marshal Voronov 7.”

“Calm down, Schmidt. - said Paulus. “So this is the order.”

“It doesn’t matter what order means when dealing with a field marshal.” And, grabbing his knife from the table, he again put it in his pocket.

A few minutes after Yakimovich’s telephone conversation with Malinin 8, the incident was over and the knives were returned to them.

Dinner was brought and everyone sat down at the table. For about 15 minutes there was silence, interrupted by individual phrases - “pass the fork, another glass of tea,” etc.

We lit cigars. “And dinner wasn’t bad at all,” noted Paulus.

“They generally cook well in Russia,” Schmidt replied.

After some time, Paulus was called to the command. “Will you go alone? - asked Schmidt. - And I?"

“They called me alone,” Paulus answered calmly.

“I won’t sleep until he returns,” Adam said, lit a new cigar and lay down on the bed in his boots. Schmidt followed his example. About an hour later Paulus returned.

“How’s the marshal?” - asked Schmidt.

"Marshal as a marshal."

“What were they talking about?”

“They offered to order those who remained to surrender, but I refused.”

“So what next?”

“I asked for our wounded soldiers. They told me that your doctors fled, and now we must take care of your wounded.”

After some time, Paulus remarked: “Do you remember this one from the NKVD with three distinctions, who accompanied us? What scary eyes he has!”

Adam replied: “It’s scary, like everyone else in the NKVD.”

The conversation ended there. The bedtime procedure began. Orderly Paulus had not yet been brought in. He opened the bed he had prepared, put two of his blankets on top, undressed and lay down.

Schmidt stirred up the whole bed with a flashlight, carefully examined the sheets (they were new, completely clean), winced with disgust, closed the blanket, said: “The pleasure begins,” covered the bed with his blanket, lay down on it, covered himself with another and said in a sharp tone: “ Turn off the lights." There were no people in the room who understood the language, no one paid attention. Then he sat up in bed and began to explain with gestures what he wanted. The lamp was wrapped in newspaper paper.

“I wonder what time we can sleep until tomorrow?” - asked Paulus.

“I’ll sleep until they wake me up,” Schmidt replied.

The night passed quietly, except for Schmidt loudly saying several times, “Don’t shake the bed.”

Nobody shook the bed. He had bad dreams.

Morning. We started shaving. Schmidt looked in the mirror for a long time and categorically declared: “It’s cold, I’ll leave the beard.”

“That’s your business, Schmidt,” Paulus remarked.

Colonel Adam, who was in the next room, muttered through his teeth: “Another originality.”

After breakfast we remembered yesterday's lunch with the commander of the 64th Army 9 .

“Did you notice how amazing the vodka was?” - said Paulus.

They were silent for a long time. The soldiers brought art. to the lieutenant the newspaper “Red Army” with the issue “In the Last Hour”. Revival. They are interested in whether their last names are indicated. Having heard the list given, they studied the newspaper for a long time and wrote their names in Russian letters on a piece of paper. We were especially interested in the trophy numbers. We paid attention to the number of tanks. “The figure is incorrect, we had no more than 150,” noted Paulus. “Perhaps they think the Russians are also” 10, answered Adam. “It wasn’t that much anyway.” They were silent for some time.

“And he, it seems, shot himself,” said Schmidt (we were talking about one of the generals).

Adam, frowning his eyebrows and staring at the ceiling: “We don’t know what’s better, isn’t captivity a mistake?”

Paulus: We'll see about that later.

Schmidt: The entire history of these four months 11 can be characterized in one phrase - you can’t jump over your head.

Adam: At home they'll think we're lost.

Paulus: In war - like in war (in French).

We started looking at the numbers again. We paid attention to the total number of people surrounded. Paulus said: Perhaps, because we knew nothing. Schmidt tries to explain to me - he draws the front line, the breakthrough, the encirclement, he says: There are many convoys, other units, they themselves did not know exactly how many.

They remain silent for half an hour, smoking cigars.

Schmidt: And in Germany, a crisis of military leadership is possible.

Nobody is answering.

Schmidt: Until mid-March they will probably advance.

Paulus: Perhaps longer.

Schmidt: Will they stay at the previous borders?

Paulus: Yes, all this will go down in military history as a brilliant example of the enemy’s operational art.

During dinner, there was constant praise for every dish served. Adam, who ate the most, was especially zealous. Paulus kept half and gave it to the orderly.

After lunch, the orderly tries to explain to Nesterov so that the penknife left with their staff doctor will be returned to him. Paulus addresses me, supplementing the German words with gestures: “The knife is a memory from Field Marshal Reichenau 12, for whom Hein was an orderly before coming to me. He was with the field marshal until his last minutes." The conversation was interrupted again. The prisoners went to bed.

Dinner. Among the dishes served on the table are coffee cookies.

Schmidt: Good cookies, probably French?

Adam: Very good, Dutch in my opinion.

They put on glasses and carefully examine the cookies.

Adam surprised: Look, Russian.

Paulus: At least stop looking at it. Ugly.

Schmidt: Please note, there are new waitresses every time.

Adam: And pretty girls.

We smoked in silence for the rest of the evening. The orderly prepared the bed and went to bed. Schmidt didn't scream at night.

Adam takes out a razor: “We’ll shave every day, we should look decent.”

Paulus: Absolutely right. I'll shave after you.

After breakfast they smoke cigars. Paulus looks out the window.

“Pay attention, Russian soldiers drop in and ask what the German field marshal looks like, but he differs from other prisoners only in his insignia.”

Schmidt: Have you noticed how much security there is? There are a lot of people, but you don’t feel like you’re in a prison. But I remember when there were captured Russian generals at the headquarters of Field Marshal Bush 13, there was no one in the room with them, the posts were on the street, and only the colonel had the right to enter them.

Paulus: That's better. It’s good that it doesn’t feel like a prison, but it’s still a prison.

All three are in a somewhat depressed mood. They speak little, smoke a lot, and think. Adam took out photographs of his wife and children and looked at them with Paulus.

Schmidt and Adam treat Paulus with respect, especially Adam.

Schmidt is closed and selfish. He even tries not to smoke his own cigars, but to buy someone else’s.

In the afternoon I went to another house, where generals Daniel 14, Drebber 15, Wultz 16 and others are located.

Completely different atmosphere and mood. They laugh a lot, Daniel tells jokes. It was not possible to hide my knowledge of the German language here, since the lieutenant colonel with whom I had spoken earlier happened to be there.

They started asking: “What is the situation, who is still in captivity, ha, ha, ha,” he said for about five minutes.

The Romanian general Dimitriu 17 sat in the corner with a gloomy look. Finally, he raised his head and asked in broken German: “Is Popescu 18 in captivity?” - Apparently, this is the most exciting question for him today.

After staying there for a few more minutes, I returned back to Paulus's house. All three were lying on their beds. Adam learned Russian by repeating out loud the Russian words he had written down on a piece of paper.

Today at 11 o'clock in the morning again at Paulus, Schmidt and Adam.

They were still sleeping when I entered. Paulus woke up and nodded his head. Schmidt woke up.

Schmidt: Good morning, what did you see in your dream?

Paulus: What dreams could a captured field marshal have? Adam, have you started shaving yet? Leave me some hot water.

The procedure of morning washing, shaving, etc. begins. Then breakfast and regular cigars.

Yesterday Paulus was summoned for questioning, he is still under his impression.

Paulus: Strange people. A captured soldier is asked about operational issues.

Schmidt: Useless thing. None of us will talk. This is not 1918, when they shouted that Germany was one thing, the government was another, and the army was another. We will not allow this mistake now.

Paulus: I completely agree with you, Schmidt.

Again they remain silent for a long time. Schmidt lies down on the bed. Falls asleep. Paulus follows his example. Adam takes out a notebook with Russian notes written down, reads it, and whispers something. Then he also goes to bed.

Suddenly Yakimovich’s car arrives. The generals are asked to go to the bathhouse. Paulus and Adam happily agree. Schmidt (he is afraid of catching a cold) also after some hesitation. Paulus' statement that Russian baths were very good and always warm had a decisive influence.

All four went to the bathhouse. Generals and Adam in a passenger car. Hein is in the back on the semi. Representatives of the headquarters security went with them.

About an hour and a half later they all returned. The impression is wonderful. They exchange lively opinions about the qualities and advantages of the Russian bath over others. They wait for dinner, so that after it they can immediately go to bed.

At this time, several cars drive up to the house. The head of the RO, Major General Vinogradov 19, enters with a translator, through whom he conveys to Paulus that he will now see all his generals who are in our captivity.

While the translator is explaining herself, I manage to find out from Vinogradov that filming is planned to chronicle the entire “captive generals.”

Despite some displeasure caused by the prospect of going out into the cold after the bath, everyone hastily gets dressed. There is a meeting with other generals coming up! They know nothing about the shooting. But the operators are already waiting near the house. Schmidt and Paulus come out. The first shots are being filmed.

Paulus: All this is already superfluous.

Schmidt: Not superfluous, but simply disgraceful (they turn away from the lenses).

They get into the car and drive to the neighboring house, where other generals are located. At the same time, the others - Colonel General Geitz 20 and others - arrive in several cars from the other side.

Meeting. The cameramen are filming feverishly. Paulus shakes hands with all his generals in turn and exchanges a few phrases: Hello, my friends, more cheerfulness and dignity.

Filming continues. The generals are divided into groups, talking animatedly. The conversation revolves mainly around the questions of who is here and who is not.

Central group - Paulus, Heitz, Schmidt The attention of the operators is directed there. Paulus is calm. Looks into the lens. Schmidt is nervous and tries to look away. When the most active operator came almost close to him, he smiled caustically and covered the lens with his hand.

The other generals hardly react to the filming. But some seem to be deliberately trying to get on film, especially next to Paulus.

Some colonel constantly walks among everyone and repeats the same phrase: “Nothing, nothing! No need to be nervous. The main thing is that everyone is alive.” Nobody pays attention to him.

The shooting ends. The departure begins. Paulus, Schmidt and Adam return home.

Schmidt: Wow, it’s a pleasure, after the bath we’ll probably catch a cold. Everything was done on purpose to make us sick.

Paulus: This shooting is even worse! A shame! Marshal (Voronov) probably knows nothing1 Such a humiliation of dignity! But nothing can be done - captivity.

Schmidt: I can’t even stomach German journalists, and then there are the Russians! Disgusting!

The conversation is interrupted by the appearance of lunch. They eat and praise the kitchen. The mood is lifted. After lunch they sleep almost until dinner. Dinner is praised again. They light a cigarette. They silently watch the smoke rings.

The sound of breaking dishes is heard in the room nearby. Hein broke the sugar bowl.

Paulus: This is Hein. Here's a teddy bear!

Schmidt: Everything is falling out of hand. I wonder how he held the steering wheel. Hein! Have you ever lost your steering wheel?

Hein: No, Lieutenant General. Then I was in a different mood.

Schmidt: Mood - mood, dishes - dishes, especially someone else's

Paulus: He was Field Marshal Reichenau's favorite. He died in his arms.

Schmidt By the way, what are the circumstances of his death?

Paulus From a heart attack after hunting and having breakfast with him. Hein, tell me in detail.

Hein: On this day, the field marshal and I went hunting. He was in a great mood and felt good. Sat down to have breakfast. I served coffee. At that moment he had a heart attack. The staff doctor said that he should be immediately taken to Leipzig to see some professor. The plane was quickly arranged. The field marshal, I, the doctor and the pilot flew off. Heading to Lviv.

The field marshal was getting worse and worse. An hour into the flight, he died on the plane.

In the future, we were generally accompanied by failures. The pilot was already landing over the Lvov airfield, but took off again. We made two more circles over the airfield. Landing the plane for the second time, for some reason, neglecting the basic rules, he landed on a black man. As a result, we crashed into one of the airfield buildings. I was the only one who made it out of this operation intact.

Again there is almost an hour of silence. They smoke and think. Paulus raises his head.

Paulus: I wonder what news?

Adam: Probably further Russian advance. Now they can do it.

Schmidt: What's next? Still the same sore point! In my opinion, this war will end even more suddenly than it began, and its end will not be military, but political. It is clear that we cannot defeat Russia, and she cannot defeat us.

Paulus: But politics is not our business. We are soldiers. The Marshal asked yesterday: why did we resist in a hopeless situation without ammunition or food? I answered him - an order! Whatever the situation, an order remains an order. We are soldiers! Discipline, order, obedience are the basis of the army. He agreed with me. And in general it’s funny, as if it was in my will to change anything.

By the way, the marshal leaves a wonderful impression. A cultured, educated person. He knows the situation very well. From Schleferer he was interested in the 29th regiment, from which no one was captured. He remembers even such little things.

Schmidt: Yes, fortune always has two sides.

Paulus: And the good thing is that you cannot predict your fate. If only I had known that I would be a field marshal and then a prisoner! In the theater, about such a play, I would say nonsense!

Starts to go to bed.

Morning. Paulus and Schmidt are still in bed. Adam enters. He had already shaved and put himself in perfect order. He extends his left hand and says: “Hail!”

Paulus: If you remember the Roman greeting, it means that you, Adam, have nothing against me. You don't have a weapon.

Adam and Schmidt laugh.

Schmidt: In Latin it sounds like “morituri tea salutam” (“those going to death greet you”).

Paulus: Just like us.

He takes out a cigarette and lights a cigarette.

Schmidt: Don’t smoke before meals, it’s harmful.

Paulus: Nothing, captivity is even more harmful.

Schmidt: We have to be patient.

They get up. Morning toilet, breakfast.

Major Ozeryansky 21 from the RO arrives to pick up Schmidt. He is called in for questioning.

Schmidt: Finally, they became interested in me (he was somewhat hurt that he had not been called earlier).

Schmidt leaves. Paulus and Adam lie down. They smoke and then sleep. Then they wait for lunch. A couple of hours later, Schmidt returns.

Schmidt: Everything is the same - why they resisted, did not agree to surrender, etc. It was very difficult to speak - a bad translator. She didn't understand me. She translated the questions in such a way that I did not understand her.

And finally, the question is my assessment of the operational art of the Russians and us. I, of course, refused to answer, saying that this was a question that could harm my homeland.

Any conversation on this topic after the war.

Paulus: That's right, I answered the same.

Schmidt: In general, I’m already tired of all this. How can they not understand that not a single German officer will go against his homeland.

Paulus: It’s simply tactless to pose such questions to us soldiers. Now no one will answer them.

Schmidt: And these pieces of propaganda are always not against the homeland, but for it, against the government, etc. I already noticed once that it was only the camels of 1918 that separated the government and the people.

Paulus: Propaganda remains propaganda! There is not even an objective course.

Schmidt: Is an objective interpretation of history even possible? Of course not. Take, for example, the question of the beginning of the war. Who started it? Who is guilty? Why? Who can answer this?

Adam: Only archives after many years.

Paulus: Soldiers were and will remain soldiers. They fight, fulfilling their duty, without thinking about the reasons, faithful to the oath. And the beginning and end of the war is the business of politicians, for whom the situation at the front prompts certain decisions.

Then the conversation turns to the history of Greece, Rome, etc. They talk about painting and archaeology. Adam talks about his participation in excavation expeditions. Schmidt, speaking about painting, authoritatively declares that German is the first in the world and the best artist in Germany is... Rembrandt 21 (allegedly because the Netherlands, Holland and Flanders are “old” German provinces).

This continues until dinner, after which they go to bed.

On the morning of February 5, I received orders to return back to the department due to redeployment. The stay with the generals is over.

Investigative officer of the KRO OO NKVD Donfront

Senior Lieutenant of State Security Tarabrin

Correct: Lieutenant Colonel P. Gapochko

AP RF, f. 52, on. 1, building 134, m. 23-33. Copy

During the Battle of Stalingrad, not only the generals mentioned in the text of the document were captured. As you know, from January 10 to February 2, 1943, the troops of the Don Front captured 24 generals, including Max Preffer - commander of the 4th Infantry Corps, von Seydlitz-Kurbach Walter, commander of the 51st Infantry Corps, Alfred Strezzius - commander of the 11th Infantry Corps, Erich Magnus - commander of the 389th Infantry Division, Otto Renoldi - chief of medical services of the 6th Army, Ulrich Vossol - chief of artillery of the 6th German Army, etc.

The document is interesting for its lively sketches, non-fictional judgments of captured German generals, captured over five days by the operative officer of the NKVD of the Don Front, senior lieutenant of state security E.A. Tarabrin.

1 Tarabrin Evgeniy Anatolyevich (1918-?) - colonel (19%). Since August 1941 - detective officer of the NKVD OO of the South-Western Stalingrad Don and Central Fronts. Since December 1942 - translator of the NKVD Organization of the Don Front. Since May 1943 - senior detective officer of the 2nd department of the 4th department of the Main Directorate of the Kyrgyz Republic "Smersh" of the Central Front. Since June 1946 - senior detective officer of the 1st department of Department 1-B

1st Main Directorate. From August 1947 - assistant to the head of the 2nd department of the 1st Directorate of the Information Committee under the USSR Council of Ministers. From December 1953 - deputy head of the sector of the 2nd Main Directorate of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs. From August 1954 - senior assistant to the head of the 1st Main Directorate of the KGB under SM USSR. Since January 1955, he was enrolled in the active reserve of the 1st Main Directorate. From August 1956 - Head of the 2nd Department of the 1st Main Directorate of the KGB under the USSR Council of Ministers. From February 1963 - Deputy Head of Service No. 2.

By KGB order No. 237 on May 18, 1965, he was dismissed under Art. 59 p. “d” (for official inconsistency).

2 Nesterov Vsevolod Viktorovich (1922-?) - senior lieutenant (1943). Since January 1943, he was a reserve detective officer of the NKVD OO of the Don Front, then the Smersh ROC of the Central Front. Since September 1943 - operational officer of the Smersh ROC of the 4th Artillery Corps of the Central Front. Since April 1944 - detective officer of the Smersh ROC of the Belorussian Front. Since August 1945 - operational officer of the Smersh ROC of the 4th Artillery Corps of the Group of Soviet Occupation Forces in Germany. Since April 1946 - operational officer of the Smersh ROC of the 12th artillery division of the 1st Rykovsky Military District, then the Moscow Military District.

By order of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs No. 366 of August 24, 1946, he was dismissed at his personal request and transferred to the register of the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

3 Schmidt Arthur (1895-?) - Lieutenant General. Chief of Staff of the 6th Army.

4 Adam Wilhelm (?-?) - adjutant of F. Paulus, colonel.

5 Bezymensky Lev Aleksandrovich, born in 1920, captain (1945). In the Red Army from August 1941, he began serving as a private in the 6th reserve engineering regiment, then a cadet in the military translator courses of the Red Army (Orsk) and the Military Institute of Foreign Languages (Stavropol). Since May 1942 - at the front, officer of the 394th separate special-purpose radio division (Southwestern Front). In January 1943, he was transferred to the intelligence department of the Don Front headquarters, where he served as a translator, senior front translator, and deputy head of the information department. Subsequently, he served in the intelligence departments of the headquarters of the Central, Belarusian, 1st Belorussian Fronts, and the intelligence department of the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany. In October 1946 he was demobilized. Afterwards he graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy of Moscow State University (1948). Worked for the magazine “New Time”. Author of a number of books, candidate of historical sciences. Professor at the Academy of Military Sciences. Awarded 6 orders and 22 medals of the USSR.

6 Rokossovsky Konstantin Konstantinovich (1896-1968) - Marshal of the Soviet Union (1944), twice Hero of the Soviet Union (1944 1945). In September 1942 - January 1943 he commanded the Don Front.

7 Voronov Nikolai Nikolaevich (1899-1968) - chief marshal of artillery (1944), Hero of the Soviet Union (1965) From July 1941 - chief of artillery of the Red Army, at the same time from September 1941 - deputy people's commissar of defense of the USSR, representative of the Supreme High Command headquarters at Stalingrad from March 1943 - commander of the artillery of the Red Army.

8 Mikhail Sergeevich Malinin (1899-1960) - Army General (1953), Hero of the Soviet Union (1945). In the Red Army since 1919. Since 1940 - chief of staff of the 7th MK. During the war - chief of staff of the 7th MK on the Western Front, the 16th Army (1941 -1942), Bryansk, Don, Central, Belorussian and 1st Belorussian fronts (1942-1945). Later - on staff work in the Soviet Army.

9 The commander of the 64th Army since August 1942 was Mikhail Stepanovich Shumilov (1895-1975) - Colonel General (1943), Hero of the Soviet Union (1943). The 64th Army, together with the 62nd Army, heroically defended Stalingrad. In April 1943 - May 1945 - commander of the 7th Guards Army. After the war, he held command positions in the Soviet Army.

10 Apparently, the press published data not only about the trophies of the 6th Army, but also about a number of other armies. In particular, the 4th German tank, 3rd and 4th Romanian, 8th Italian armies.

11 Most likely, the chief of staff of the 6th Army A. Schmidt is referring to the period when the counteroffensive in the Stalingrad direction of troops of three fronts began. South-Western, Don and Stalingrad and the encirclement of the 6th Army and part of the 4th Tank Army was completed.

12 Reichenau Walter von (1884-1942) - Field Marshal General (1940). Commanded the 6th Army in 1939-1941. Since December 1941 - commander of Army Group South on the Soviet-German front. Died of a heart attack.

13 Bush Ernst Von (1885-1945) - Field Marshal General (1943). In 1941, he commanded the 16th Army on the Soviet-German front. In 1943-1944. - Commander of the Army Group "Center".

14 Daniels Alexander Von (1891-?) - Lieutenant General (1942), commander of the 376th division.

15 Drebber Moritz Von (1892-?) - Major General of Infantry (1943), commander of the 297th Infantry Division.

16 Hans Wultz (1893-?) - Major General of Artillery (1942).

17 Dimitriu - commander of the 2nd Romanian Infantry Division, major general.

18 Apparently, we are talking about Dimitar Popescu, general, commander of the 5th Cavalry Division.

19 Ilya Vasilievich Vinogradov (1906-1978) - Lieutenant General (1968) (see Vol. 2 of this collection, document No. 961).

20 Heitz (Heitz) Walter (1878-?) - Colonel General (1943).

21 Ozeryansky Evsey (Evgeniy) (1911-?), colonel (1944). In the Red Army from December 1933 to March 1937 and from August 10, 1939. In June 1941 - battalion commissar, senior instructor of the organizational training department of the political department of the Kyiv Special Military District. From July 1, 1941 - in the same position in the political department of the Southwestern Front. From November 22, 1941 - head of the organizational department of the political department of the 21st Army; from December 1941 - deputy chief of the political department of the 21st Army. On April 14, 1942, he was transferred to the position of military commissar - deputy chief for political affairs of the intelligence department of the headquarters of the South-Western, then until the end of the Great Patriotic War - the Don Central, 1st Belorussian fronts. In the post-war years - on political work in the Carpathian and Odessa military districts.

Transferred to the reserve on March 19, 1958. Awarded three Orders of the Red Banner, the Order of Bohdan Khmelnitsky, the Order of the Patriotic War 1st degree, the Red Star, and other orders and medals.

22 Rembrandt Harmensz van Ryn (1606-1669) - Dutch painter, draftsman, etcher.

During the Great Patriotic War, about three and a half million soldiers were captured by the Soviets, who were later tried for various war crimes. This number included both the Wehrmacht military and their allies. Moreover, more than two million are Germans. Almost all of them were found guilty and received significant prison sentences. Among the prisoners there were also “big fish” - high-ranking and far from ordinary representatives of the German military elite.

However, the vast majority of them were kept in quite acceptable conditions and were able to return to their homeland. Soviet troops and the population treated the defeated invaders quite tolerantly. "RG" talks about the most senior Wehrmacht and SS officers who were captured by the Soviets.

Field Marshal Friedrich Wilhelm Ernst Paulus

Paulus was the first of the German high military ranks to be captured. During the Battle of Stalingrad, all members of his headquarters - 44 generals - were captured along with him.

On January 30, 1943 - the day before the complete collapse of the encircled 6th Army - Paulus was awarded the rank of Field Marshal. The calculation was simple - not a single top commander in the entire history of Germany surrendered. Thus, the Fuhrer intended to push his newly appointed field marshal to continue resistance and, as a result, commit suicide. Having thought about this prospect, Paulus decided in his own way and ordered an end to resistance.

Despite all the rumors about the “atrocities” of the communists towards prisoners, the captured generals were treated with great dignity. Everyone was immediately taken to the Moscow region - to the Krasnogorsk operational transit camp of the NKVD. The security officers intended to win the high-ranking prisoner over to their side. However, Paulus resisted for quite a long time. During interrogations, he declared that he would forever remain a National Socialist.

It is believed that Paulus was one of the founders of the National Committee of Free Germany, which immediately launched active anti-fascist activities. In fact, when the committee was created in Krasnogorsk, Paulus and his generals were already in the general’s camp in the Spaso-Evfimiev Monastery in Suzdal. He immediately regarded the work of the committee as “betrayal.” He called the generals who agreed to cooperate with the Soviets traitors, whom he “can no longer consider as his comrades.”

Paulus changed his point of view only in August 1944, when he signed an appeal “To prisoners of war German soldiers, officers and the German people.” In it, he called for the removal of Adolf Hitler and an end to the war. Immediately after this, he joined the anti-fascist Union of German Officers, and then Free Germany. There he soon became one of the most active propagandists.

Historians are still arguing about the reasons for such a sharp change in position. Most attribute this to the defeats that the Wehrmacht had suffered by that time. Having lost the last hope for German success in the war, the former field marshal and current prisoner of war decided to side with the winner. One should not dismiss the efforts of the NKVD officers, who methodically worked with “Satrap” (Paulus’s pseudonym). By the end of the war, they practically forgot about him - he couldn’t really help, the Wehrmacht front was already cracking in the East and West.

After the defeat of Germany, Paulus came in handy again. He became one of the main witnesses for the Soviet prosecution at the Nuremberg trials. Ironically, it was captivity that may have saved him from the gallows. Before his capture, he enjoyed the Fuhrer’s enormous trust; he was even predicted to replace Alfred Jodl, the chief of staff of the operational leadership of the Wehrmacht High Command. Jodl, as is known, became one of those whom the tribunal sentenced to hang for war crimes.

After the war, Paulus, along with other “Stalingrad” generals, continued to be captured. Most of them were released and returned to Germany (only one died in captivity). Paulus continued to be kept at his dacha in Ilyinsk, near Moscow.

He was able to return to Germany only after Stalin's death in 1953. Then, by order of Khrushchev, the former military man was given a villa in Dresden, where he died on February 1, 1957. It is significant that at his funeral, in addition to his relatives, only party leaders and generals of the GDR were present.

General of Artillery Walter von Seydlitz-Kurzbach

The aristocrat Seydlitz commanded the corps in Paulus's army. He surrendered on the same day as Paulus, albeit on a different sector of the front. Unlike his commander, he began to cooperate with counterintelligence almost immediately. It was Seydlitz who became the first chairman of Free Germany and the Union of German Officers. He even suggested that the Soviet authorities form German units to fight the Nazis. True, prisoners were no longer considered as a military force. They were used only for propaganda work.

After the war, Seydlitz remained in Russia. At a dacha near Moscow, he advised the creators of a film about the Battle of Stalingrad and wrote memoirs. Several times he asked for repatriation to the territory of the Soviet zone of occupation of Germany, but was refused each time.

In 1950, he was arrested and sentenced to 25 years in prison. The former general was kept in solitary confinement.

Seydlitz received his freedom in 1955 after the visit of German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer to the USSR. After his return, he led a reclusive life.

Lieutenant General Vinzenz Müller

For some, Müller went down in history as the “German Vlasov.” He commanded the 4th German Army, which was completely defeated near Minsk. Müller himself was captured. From the very first days as a prisoner of war he joined the work of the Union of German Officers.

For some special merits, he not only was not convicted, but immediately after the war he returned to Germany. That's not all - he was appointed Deputy Minister of Defense. Thus, he became the only major Wehrmacht commander who retained his rank of lieutenant general in the GDR army.

In 1961, Müller fell from the balcony of his house in a suburb of Berlin. Some claimed it was suicide.

Grand Admiral Erich Johann Albert Raeder

Until the beginning of 1943, Raeder was one of the most influential military men in Germany. He served as commander of the Kriegsmarine (German Navy). After a series of failures at sea, he was removed from his post. He received the position of chief inspector of the fleet, but had no real powers.

Erich Raeder was captured in May 1945. During interrogations in Moscow, he spoke about all the preparations for war and gave detailed testimony.

Initially, the USSR intended to try the former grand admiral itself (Raeder is one of the few who was not considered at the conference in Yalta, where the issue of punishing war criminals was discussed), but later a decision was made on his participation in the Nuremberg trials. The tribunal sentenced him to life imprisonment. Immediately after the verdict was announced, he demanded that the sentence be changed to execution, but was refused.

He was released from Spandau prison in January 1955. The official reason was the prisoner's health condition. The illness did not stop him from writing his memoirs. He died in Kiel in November 1960.

SS Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke

The commander of the 1st SS Panzer Division "Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler" is one of the few SS generals captured by Soviet troops. The overwhelming number of SS men made their way to the west and surrendered to the Americans or British. On April 21, 1945, Hitler appointed him commander of a “battle group” for the defense of the Reich Chancellery and the Fuhrer’s bunker. After the collapse of Germany, he tried to break out of Berlin to the north with his soldiers, but was captured. By that time, almost his entire group was destroyed.

After signing the act of surrender, Monke was taken to Moscow. There he was held first in Butyrka, and then in Lefortovo prison. The sentence - 25 years in prison - was heard only in February 1952. He served his sentence in the legendary pre-trial detention center No. 2 of the city of Vladimir - “Vladimir Central”.

The former general returned to Germany in October 1955. At home he worked as a sales agent selling trucks and trailers. He died quite recently - in August 2001.

Until the end of his life, he considered himself an ordinary soldier and actively participated in the work of various associations of SS military personnel.

SS Brigadeführer Helmut Becker

SS man Becker was brought into Soviet captivity by his place of service. In 1944, he was appointed commander of the Totenkopf (Death's Head) division, becoming its last commander. According to the agreement between the USSR and the USA, all military personnel of the division were subject to transfer to Soviet troops.

Before the defeat of Germany, Becker, confident that only death awaited him in the east, tried to break through to the west. Having led his division through the whole of Austria, he capitulated only on May 9. Within a few days he found himself in Poltava prison.

In 1947, he appeared before the military tribunal of the troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Kyiv Military District and received 25 years in the camps. Apparently, like all other German prisoners of war, he could return to Germany in the mid-50s. However, he became one of the few top German military commanders to die in the camp.

The cause of Becker’s death was not hunger and overwork, which was common in the camps, but a new accusation. In the camp he was tried for sabotage of construction work. On September 9, 1952, he was sentenced to death. Already on February 28 of the following year he was shot.

General of Artillery Helmut Weidling

The commander of the defense and the last commandant of Berlin was captured during the assault on the city. Realizing the futility of resistance, he gave the order to cease hostilities. He tried in every possible way to cooperate with the Soviet command and personally signed the act of surrender of the Berlin garrison on May 2.

The general’s tricks did not help save him from trial. In Moscow he was kept in Butyrskaya and Lefortovo prisons. After this he was transferred to the Vladimir Central.

The last commandant of Berlin was sentenced in 1952 - 25 years in the camps (the standard sentence for Nazi criminals).

Weidling was no longer able to be released. He died of heart failure on November 17, 1955. He was buried in the prison cemetery in an unmarked grave.

SS-Obergruppenführer Walter Krueger

Since 1944, Walter Kruger led the SS troops in the Baltic states. He continued to fight until the very end of the war, but eventually tried to break into Germany. With fighting I reached almost the very border. However, on May 22, 1945, Kruger’s group attacked a Soviet patrol. Almost all the Germans died in the battle.

Kruger himself was taken alive - after being wounded, he was unconscious. However, it was not possible to interrogate the general - when he came to his senses, he shot himself. As it turned out, he kept a pistol in a secret pocket, which could not be found during the search.

SS Gruppenführer Helmut von Pannwitz

Von Pannwitz is the only German who was tried along with the White Guard generals Shkuro, Krasnov and other collaborators. This attention is due to all the activities of the cavalryman Pannwitz during the war. It was he who oversaw the creation of Cossack troops in the Wehrmacht on the German side. He was also accused of numerous war crimes in the Soviet Union.

Therefore, when Pannwitz, together with his brigade, surrendered to the British, the USSR demanded his immediate extradition. In principle, the Allies could refuse - as a German, Pannwitz was not subject to trial in the Soviet Union. However, given the severity of the crimes (there was evidence of numerous executions of civilians), the German general was sent to Moscow along with the traitors.

In January 1947, the court sentenced all the accused (six people were in the dock) to death. A few days later, Pannwitz and other leaders of the anti-Soviet movement were hanged.

Since then, monarchist organizations have regularly raised the issue of rehabilitating those hanged. Time after time, the Supreme Court makes a negative decision.

SS Sturmbannführer Otto Günsche

By his rank (the army equivalent is major), Otto Günsche, of course, did not belong to the German army elite. However, due to his position, he was one of the most knowledgeable people about life in Germany at the end of the war.

For several years, Günsche was Adolf Hitler's personal adjutant. It was he who was tasked with destroying the body of the Fuhrer who committed suicide. This became a fatal event in the life of the young (at the end of the war he was not even 28 years old) officer.

Gunsche was captured by the Soviets on May 2, 1945. Almost immediately he found himself in the development of SMERSH agents, who were trying to find out the fate of the missing Fuhrer. Some of the materials are still classified.

Finally, in 1950, Otto Günsche was sentenced to 25 years in prison. However, in 1955 he was transported to serve his sentence in the GDR, and a year later he was completely released from prison. Soon he moved to Germany, where he remained for the rest of his life. He died in 2003.

I. SOVIET COMMANDERS AND MILITARY LEADERS.

1. Generals and military leaders of the strategic and operational-strategic level.

Zhukov Georgy Konstantinovich (1896-1974)- Marshal of the Soviet Union, Deputy Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the USSR Armed Forces, member of the Supreme Command Headquarters. He commanded the troops of the Reserve, Leningrad, Western, and 1st Belorussian fronts, coordinated the actions of a number of fronts, and made a great contribution to achieving victory in the battle of Moscow, in the Battles of Stalingrad, Kursk, in the Belarusian, Vistula-Oder and Berlin operations.

Vasilevsky Alexander Mikhailovich (1895-1977)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. Chief of the General Staff in 1942-1945, member of the Supreme Command Headquarters. He coordinated the actions of a number of fronts in strategic operations, in 1945 - commander of the 3rd Belorussian Front and commander-in-chief of Soviet troops in the Far East.

Rokossovsky Konstantin Konstantinovich (1896-1968)- Marshal of the Soviet Union, Marshal of Poland. Commanded the Bryansk, Don, Central, Belorussian, 1st and 2nd Belorussian fronts.

Konev Ivan Stepanovich (1897-1973)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. Commanded the troops of the Western, Kalinin, North-Western, Steppe, 2nd and 1st Ukrainian Fronts.

Malinovsky Rodion Yakovlevich (1898-1967)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. From October 1942 - Deputy Commander of the Voronezh Front, Commander of the 2nd Guards Army, Southern, Southwestern, 3rd and 2nd Ukrainian, Transbaikal Fronts.

Govorov Leonid Alexandrovich (1897-1955)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. From June 1942 he commanded the troops of the Leningrad Front, and in February-March 1945 he simultaneously coordinated the actions of the 2nd and 3rd Baltic Fronts.

Antonov Alexey Innokentievich (1896-1962)- army General. Since 1942 - first deputy chief, chief (since February 1945) of the General Staff, member of the Supreme Command Headquarters.

Timoshenko Semyon Konstantinovich (1895-1970)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. During the Great Patriotic War - People's Commissar of Defense of the USSR, member of the Supreme Command Headquarters, Commander-in-Chief of the Western and South-Western directions, from July 1942 he commanded the Stalingrad and North-Western Fronts. Since 1943 - representative of the Supreme Command Headquarters at the fronts.

Tolbukhin Fedor Ivanovich (1894-1949)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. At the beginning of the war - chief of staff of the district (front). Since 1942 - Deputy Commander of the Stalingrad Military District, Commander of the 57th and 68th Armies, Southern, 4th and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts.

Meretskov Kirill Afanasyevich (1897-1968)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. At the beginning of the war, he was a representative of the Supreme Command Headquarters on the Volkhov and Karelian fronts, commanding the 7th and 4th armies. Since December 1941 - commander of the troops of the Volkhov, Karelian and 1st Far Eastern fronts. He particularly distinguished himself during the defeat of the Japanese Kwantung Army in 1945.

Shaposhnikov Boris Mikhailovich (1882-1945)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. Member of the Supreme Command Headquarters, Chief of the General Staff during the most difficult period of defensive operations in 1941. He made an important contribution to the organization of the defense of Moscow and the transition of the Red Army to the counteroffensive. From May 1942 - Deputy People's Commissar of Defense of the USSR, Head of the Military Academy of the General Staff.

Chernyakhovsky Ivan Danilovich (1906-1945)- army General. He commanded the tank corps, the 60th Army, and from April 1944 the 3rd Belorussian Front. Mortally wounded in February 1945.

Vatutin Nikolai Fedorovich (1901-1944)- army General. From June 1941 - Chief of Staff of the North-Western Front, First Deputy Chief of the General Staff, Commander of the Voronezh, South-Western and 1st Ukrainian Fronts. He showed the highest art of military leadership in the Battle of Kursk, during the crossing of the river. Dnieper and the liberation of Kyiv, in the Korsun-Shevchenko operation. Mortally wounded in battle in February 1944.

Bagramyan Ivan Khristoforovich (1897-1982)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. Chief of Staff of the South-Western Front, then at the same time of the headquarters of the troops of the South-Western direction, commander of the 16th (11th Guards) Army. Since 1943, he commanded the troops of the 1st Baltic and 3rd Belorussian fronts.

Eremenko Andrey Ivanovich (1892-1970)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. Commanded the Bryansk Front, the 4th Shock Army, the South-Eastern, Stalingrad, Southern, Kalinin, 1st Baltic Fronts, the Separate Primorsky Army, the 2nd Baltic and 4th Ukrainian Fronts. He particularly distinguished himself in the Battle of Stalingrad.

Petrov Ivan Efimovich (1896-1958)- army General. Since May 1943 - commander of the North Caucasus Front, 33rd Army, 2nd Belorussian and 4th Ukrainian Fronts, chief of staff of the 1st Ukrainian Front.

2. Naval commanders of the strategic and operational-strategic level.

Kuznetsov Nikolay Gerasimovich (1902-1974)- Admiral of the Fleet of the Soviet Union. People's Commissar of the Navy in 1939-1946, Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, member of the Supreme Command Headquarters. Ensured the organized entry of naval forces into the war.

Isakov Ivan Stepanovich (1894-1967)- Admiral of the Fleet of the Soviet Union. In 1938-1946. - Deputy and First Deputy People's Commissar of the Navy, simultaneously in 1941-1943. Chief of the Main Staff of the Navy. Ensured successful management of fleet forces during the war.

Tributs Vladimir Filippovich (1900-1977)- admiral. Commander of the Baltic Fleet in 1939-1947. He showed courage and skillful actions during the relocation of the Baltic Fleet Forces from Tallinn to Kronstadt and during the defense of Leningrad.

Golovko Arseny Grigorievich (1906-1962)- Admiral. In 1940-1946. - Commander of the Northern Fleet. Provided (together with the Karelian Front) reliable cover of the flank of the Soviet Armed Forces and sea communications for allied supplies.

Oktyabrsky (Ivanov) Philip Sergeevich (1899-1969)- admiral. Commander of the Black Sea Fleet from 1939 to June 1943 and from March 1944. From June 1943 to March 1944 - Commander of the Amur Military Flotilla. Ensured the organized entry into the war of the Black Sea Fleet and successful actions during the war.

3. Commanders of combined arms armies.

Chuikov Vasily Ivanovich (1900-1982)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. Since September 1942 - commander of the 62nd (8th Guards) Army. He particularly distinguished himself in the Battle of Stalingrad.

Batov Pavel Ivanovich (1897-1985)- army General. Commander of the 51st, 3rd armies, assistant commander of the Bryansk Front, commander of the 65th army.

Beloborodov Afanasy Pavlantievich (1903-1990)- army General. Since the beginning of the war - commander of a division, rifle corps. Since 1944 - commander of the 43rd, in August-September 1945 - 1st Red Banner Army.

Grechko Andrey Antonovich (1903-1976)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. From April 1942 - commander of the 12th, 47th, 18th, 56th armies, deputy commander of the Voronezh (1st Ukrainian) Front, commander of the 1st Guards Army.

Krylov Nikolai Ivanovich (1903-1972)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. From July 1943 he commanded the 21st and 5th armies. He had unique experience in the defense of besieged large cities, being the chief of staff of the defense of Odessa, Sevastopol and Stalingrad.

Moskalenko Kirill Semenovich (1902-1985)- Marshal of the Soviet Union. Since 1942, he commanded the 38th, 1st Tank, 1st Guards and 40th armies.

Pukhov Nikolai Pavlovich (1895-1958)- Colonel General. In 1942-1945. commanded the 13th Army.

Chistyakov Ivan Mikhailovich (1900-1979)- Colonel General. In 1942-1945. commanded the 21st (6th Guards) and 25th armies.

Gorbatov Alexander Vasilievich (1891-1973)- army General. Since June 1943 - commander of the 3rd Army.

Kuznetsov Vasily Ivanovich (1894-1964)- Colonel General. During the war years he commanded the troops of the 3rd, 21st, 58th, 1st Guards Armies; since 1945 - commander of the 3rd Shock Army.

Luchinsky Alexander Alexandrovich (1900-1990)- army General. Since 1944 - commander of the 28th and 36th armies. He especially distinguished himself in the Belarusian and Manchurian operations.

Lyudnikov Ivan Ivanovich (1902-1976)- Colonel General. During the war he commanded a rifle division and corps, and in 1942 he was one of the heroic defenders of Stalingrad. Since May 1944 - commander of the 39th Army, which participated in the Belarusian and Manchurian operations.

Galitsky Kuzma Nikitovich (1897-1973)- army General. Since 1942 - commander of the 3rd shock and 11th guards armies.

Zhadov Alexey Semenovich (1901-1977)- army General. Since 1942 he commanded the 66th (5th Guards) Army.

Glagolev Vasily Vasilievich (1896-1947)- Colonel General. Commanded the 9th, 46th, 31st, and in 1945 the 9th Guards armies. He distinguished himself in the Battle of Kursk, the battle for the Caucasus, during the crossing of the Dnieper, and the liberation of Austria and Czechoslovakia.

Kolpakchi Vladimir Yakovlevich (1899-1961)- army General. Commanded the 18th, 62nd, 30th, 63rd, 69th armies. He acted most successfully in the Vistula-Oder and Berlin operations.

Pliev Issa Alexandrovich (1903-1979)- army General. During the war - commander of guards cavalry divisions, corps, commander of cavalry mechanized groups. He particularly distinguished himself by his bold and daring actions in the Manchurian strategic operation.

Fedyuninsky Ivan Ivanovich (1900-1977)- army General. During the war years, he was commander of the 32nd and 42nd armies, the Leningrad Front, 54th and 5th armies, deputy commander of the Volkhov and Bryansk fronts, commander of the 11th and 2nd shock armies.

Belov Pavel Alekseevich (1897-1962)- Colonel General. Commanded the 61st Army. He was distinguished by decisive maneuvering actions during the Belarusian, Vistula-Oder and Berlin operations.

Shumilov Mikhail Stepanovich (1895-1975)- Colonel General. From August 1942 until the end of the war, he commanded the 64th Army (from 1943 - the 7th Guards), which, together with the 62nd Army, heroically defended Stalingrad.

Berzarin Nikolai Erastovich (1904-1945)- Colonel General. Commander of the 27th and 34th armies, deputy commander of the 61st and 20th armies, commander of the 39th and 5th shock armies. He particularly distinguished himself by his skillful and decisive actions in the Berlin operation.

4. Commanders of tank armies.

Katukov Mikhail Efimovich (1900-1976)- Marshal of the Armored Forces. One of the founders of the Tank Guard is the commander of the 1st Guards Tank Brigade, 1st Guards Tank Corps. Since 1943 - commander of the 1st Tank Army (since 1944 - Guards Army).

Bogdanov Semyon Ilyich (1894-1960)- Marshal of the Armored Forces. Since 1943, he commanded the 2nd (since 1944 - Guards) Tank Army.

Rybalko Pavel Semenovich (1894-1948)- Marshal of the Armored Forces. From July 1942 he commanded the 5th, 3rd and 3rd Guards Tank Armies.

Lelyushenko Dmitry Danilovich (1901-1987)- army General. From October 1941 he commanded the 5th, 30th, 1st, 3rd Guards, 4th Tank (from 1945 - Guards) armies.

Rotmistrov Pavel Alekseevich (1901-1982)- Chief Marshal of the Armored Forces. He commanded a tank brigade and a corps and distinguished himself in the Stalingrad operation. Since 1943 he commanded the 5th Guards Tank Army. Since 1944 - Deputy Commander of the armored and mechanized forces of the Soviet Army.

Kravchenko Andrey Grigorievich (1899-1963)- Colonel General of Tank Forces. Since 1944 - commander of the 6th Guards Tank Army. He showed an example of highly maneuverable, rapid actions during the Manchurian strategic operation.

5. Aviation military leaders.

Novikov Alexander Alexandrovich (1900-1976)- Air Chief Marshal. Commander of the Air Force of the Northern and Leningrad Fronts, Deputy People's Commissar of Defense of the USSR for Aviation, Commander of the Air Force of the Soviet Army.

Rudenko Sergey Ignatievich (1904-1990)- Air Marshal, commander of the 16th Air Army since 1942. He paid great attention to training combined arms commanders in the combat use of aviation.

Krasovsky Stepan Akimovich (1897-1983)- Air Marshal. During the war - commander of the Air Force of the 56th Army, Bryansk and Southwestern Fronts, 2nd and 17th Air Armies.

Vershinin Konstantin Andreevich (1900-1973)- Air Chief Marshal. During the war - commander of the Air Force of the Southern and Transcaucasian fronts and the 4th Air Army. Along with effective actions to support the front troops, he paid special attention to the fight against enemy aviation and gaining air supremacy.

Sudets Vladimir Alexandrovich (1904-1981)- Air Marshal. Commander of the Air Force of the 51st Army, Air Force of the Military District, since March 1943 - 17th Air Army.

Golovanov Alexander Evgenievich (1904-1975)- Air Chief Marshal. From 1942 he commanded long-range aviation, and from 1944 - the 18th Air Army.

Khryukin Timofey Timofeevich (1910-1953)- Colonel General of Aviation. Commanded the Air Forces of the Karelian and Southwestern Fronts, the 8th and 1st Air Armies.

Zhavoronkov Semyon Fedorovich (1899-1967)- Air Marshal. During the war he was commander of naval aviation. Ensured the survivability of naval aviation at the beginning of the war, the increase in its efforts and skillful combat use during the war.

6. Artillery commanders.

Voronov Nikolai Nikolaevich (1899-1968)- Chief Marshal of Artillery. During the war years - head of the country's Main Air Defense Directorate, chief of artillery of the Soviet Army - deputy people's commissar of defense of the USSR. Since 1943 - commander of the artillery of the Soviet Army, representative of the Supreme Command Headquarters on the fronts during the Stalingrad and a number of other operations. He developed the most advanced theory and practice of the combat use of artillery for his time, incl. artillery offensive, for the first time in history created a reserve of the Supreme High Command, which made it possible to maximize the use of artillery.

Kazakov Nikolai Nikolaevich (1898-1968)- Marshal of Artillery. During the war - chief of artillery of the 16th Army, Bryansk, Don, commander of artillery of the Central, Belorussian and 1st Belorussian fronts. One of the highest class masters in organizing an artillery offensive.

Nedelin Mitrofan Ivanovich (1902-1960)- Chief Marshal of Artillery. During the war - chief of artillery of the 37th and 56th armies, commander of the 5th artillery corps, commander of the artillery of the Southwestern and 3rd Ukrainian fronts.

Odintsov Georgy Fedotovich (1900-1972)- Marshal of Artillery. With the beginning of the war - chief of staff and chief of artillery of the army. From May 1942 - commander of the artillery of the Leningrad Front. One of the largest specialists in organizing the fight against enemy artillery.

II. COMMANDERS AND MILITARY LEADERS OF THE ALLIED ARMIES OF THE USA

Eisenhower Dwight David (1890-1969)- American statesman and military leader, army general. Commander of American forces in Europe since 1942, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces in Western Europe in 1943-1945.

MacArthur Douglas (1880-1964)- army General. Commander of the US armed forces in the Far East in 1941-1942, since 1942 - commander of the allied forces in the southwestern part of the Pacific Ocean.

Marshall George Catlett (1880-1959)- army General. Chief of Staff of the US Army in 1939-1945, one of the main authors of the military-strategic plans of the US and Great Britain in World War II.

Lehi William (1875-1959)- Admiral of the Fleet. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, at the same time - Chief of Staff to the Supreme Commander of the US Armed Forces in 1942-1945.

Halsey William (1882-1959)- Admiral of the Fleet. He commanded the 3rd Fleet and led American forces in the battle for the Solomon Islands in 1943.

Patton George Smith Jr. (1885-1945)- general. Since 1942, he commanded an operational group of troops in North Africa, in 1944-1945. - The 7th and 3rd American armies in Europe, skillfully used tank forces.

Bradley Omar Nelson (1893-1981)- army General. Commander of the 12th Army Group of the Allied Forces in Europe in 1942-1945.

King Ernest (1878-1956)- Admiral of the Fleet. Commander-in-Chief of the US Navy, Chief of Naval Operations 1942-1945.

Nimitz Chester (1885-1966)- admiral. Commander of US Forces in the Central Pacific from 1942-1945.

Arnold Henry (1886-1950)- army General. In 1942-1945. - Chief of Staff of the US Army Air Forces.

Clark Mark (1896-1984)- general. Commander of the 5th American Army in Italy in 1943-1945. He became famous for his landing operation in the Salerno area (Operation Avalanche).

Spaats Karl (1891-1974)- general. Commander of US Strategic Air Forces in Europe. He led strategic aviation operations during the air offensive against Germany.

Great Britain

Montgomery Bernard Law (1887-1976)- Field Marshal. Since July 1942 - commander of the 8th British Army in Africa. During the Normandy operation he commanded an army group. In 1945 - Commander-in-Chief of the British occupation forces in Germany.

Brooke Alan Francis (1883-1963)- Field Marshal. Commanded the British Army Corps in France in 1940-1941. troops of the metropolis. In 1941-1946. - Chief of the Imperial General Staff.

Alexander Harold (1891-1969)- Field Marshal. In 1941-1942. commander of British troops in Burma. In 1943, he commanded the 18th Army Group in Tunisia and the 15th Allied Army Group that landed on the island. Sicily and Italy. Since December 1944 - Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations.

Cunningham Andrew (1883-1963)- admiral. Commander of the British fleet in the eastern Mediterranean in 1940-1941.

Harris Arthur Travers (1892-1984)- Air Marshal. Commander of the bomber force that carried out the “air offensive” against Germany in 1942-1945.

Tedder Arthur (1890-1967)- Air Chief Marshal. Eisenhower's Deputy Supreme Allied Commander in Europe for Aviation during the Second Front in Western Europe in 1944-1945.

Wavell Archibald (1883-1950)- Field Marshal. Commander of British troops in East Africa in 1940-1941. In 1942-1945. - Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces in Southeast Asia.

France

De Tassigny Jean de Lattre (1889-1952)- Marshal of France. Since September 1943 - Commander-in-Chief of the troops of "Fighting France", since June 1944 - Commander of the 1st French Army.

Juin Alphonse (1888-1967)- Marshal of France. Since 1942 - commander of the troops of "Fighting France" in Tunisia. In 1944-1945 - commander of the French expeditionary force in Italy.

China

Zhu De (1886-1976)- Marshal of the People's Republic of China. During the national liberation war of the Chinese people 1937-1945. commanded the 8th Army operating in Northern China. Since 1945 - Commander-in-Chief of the People's Liberation Army of China.

Peng Dehuai (1898-1974)- Marshal of the People's Republic of China. In 1937-1945. - Deputy Commander of the 8th Army of the PLA.

Chen Yi- Commander of the New 4th Army of the PLA, operating in the regions of Central China.

Liu Bochen- Commander of the PLA unit.

Poland

Michal Zymierski (pseudonym - Rolya) (1890-1989)- Marshal of the People's Republic of Poland. During the Nazi occupation of Poland he participated in the Resistance movement. From January 1944 - Commander-in-Chief of the Army of Ludova, from July 1944 - Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Army.

Berling Sigmund (1896-1980)- General of the Armor of the Polish Army. In 1943 - organizer on the territory of the USSR of the 1st Polish Infantry Division named after. Kosciuszko, in 1944 - commander of the 1st Army of the Polish Army.

Poplavsky Stanislav Gilarovich (1902-1973)- General of the Army (in the Soviet Armed Forces). During the war years in the Soviet Army - commander of a regiment, division, corps. Since 1944, in the Polish Army - commander of the 2nd and 1st armies.

Swierczewski Karol (1897-1947)- General of the Polish Army. One of the organizers of the Polish Army. During the Great Patriotic War - commander of a rifle division, from 1943 - deputy commander of the 1st Polish Corps of the 1st Army, from September 1944 - commander of the 2nd Army of the Polish Army.

Czechoslovakia

Svoboda Ludwik (1895-1979)- statesman and military leader of the Czechoslovak Republic, army general. One of the initiators of the creation of Czechoslovak units on the territory of the USSR, since 1943 - commander of a battalion, brigade, 1st Army Corps.

III. THE MOST PROMINENT COMMANDERS AND NAVAL LEADERS OF THE GREAT PATRIOTIC WAR (FROM THE ENEMY SIDE)

Germany

Rundstedt Karl Rudolf (1875-1953)- Field Marshal General. During World War II, he commanded Army Group South and Army Group A in the attack on Poland and France. He headed Army Group South on the Soviet-German front (until November 1941). From 1942 to July 1944 and from September 1944 - Commander-in-Chief of German troops in the West.

Manstein Erich von Lewinsky (1887-1973)- Field Marshal General. In the French campaign of 1940 he commanded a corps, on the Soviet-German front - a corps, an army, in 1942-1944. - Army Group "Don" and "South".

Keitel Wilhelm (1882-1946)- Field Marshal General. In 1938-1945. - Chief of Staff of the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces.

Kleist Ewald (1881-1954)- Field Marshal General. During World War II, he commanded a tank corps and a tank group operating against Poland, France, and Yugoslavia. On the Soviet-German front he commanded a tank group (army), in 1942-1944. - Army Group A.

Guderian Heinz Wilhelm (1888-1954)- Colonel General. During World War II he commanded a tank corps, a group and an army. In December 1941, after the defeat near Moscow, he was removed from office. In 1944-1945 - Chief of the General Staff of the Ground Forces.

Rommel Erwin (1891-1944)- Field Marshal General. In 1941-1943. commanded the German Expeditionary Forces in North Africa, Army Group B in Northern Italy, 1943-1944. - Army Group B in France.

Dönitz Karl (1891-1980)- Grand Admiral. Commander of the submarine fleet (1936-1943), commander-in-chief of the Navy of Nazi Germany (1943-1945). At the beginning of May 1945 - Reich Chancellor and Supreme Commander.

Keselring Albert (1885-1960)- Field Marshal General. He commanded air fleets operating against Poland, Holland, France, and England. At the beginning of the war with the USSR, he commanded the 2nd Air Fleet. From December 1941 - Commander-in-Chief of the Nazi forces of the South-West (Mediterranean - Italy), in 1945 - the troops of the West (West Germany).

Finland

Mannerheim Carl Gustav Emil (1867-1951)- Finnish military and statesman, marshal. Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish army in the wars against the USSR in 1939-1940. and 1941-1944

Japan

Yamamoto Isoroku (1884-1943)- admiral. During World War II - Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Navy. Carried out the operation to defeat the American fleet at Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

The names of some are still honored, the names of others are consigned to oblivion. But they are all united by their leadership talent.

USSR

Zhukov Georgy Konstantinovich (1896–1974)

Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Zhukov had the opportunity to take part in serious hostilities shortly before the start of World War II. In the summer of 1939, Soviet-Mongolian troops under his command defeated the Japanese group on the Khalkhin Gol River.

By the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, Zhukov headed the General Staff, but was soon sent to the active army. In 1941, he was assigned to the most critical sectors of the front. Restoring order in the retreating army with the most stringent measures, he managed to prevent the Germans from capturing Leningrad, and to stop the Nazis in the Mozhaisk direction on the outskirts of Moscow. And already at the end of 1941 - beginning of 1942, Zhukov led a counter-offensive near Moscow, pushing the Germans back from the capital.

In 1942-43, Zhukov did not command individual fronts, but coordinated their actions as a representative of the Supreme High Command at Stalingrad, on the Kursk Bulge, and during the breaking of the siege of Leningrad.

At the beginning of 1944, Zhukov took command of the 1st Ukrainian Front instead of the seriously wounded General Vatutin and led the Proskurov-Chernovtsy offensive operation he planned. As a result, Soviet troops liberated most of Right Bank Ukraine and reached the state border.

At the end of 1944, Zhukov led the 1st Belorussian Front and led an attack on Berlin. In May 1945, Zhukov accepted the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany, and then two Victory Parades, in Moscow and Berlin.

After the war, Zhukov found himself in a supporting role, commanding various military districts. After Khrushchev came to power, he became deputy minister and then headed the Ministry of Defense. But in 1957 he finally fell into disgrace and was removed from all posts.

Rokossovsky Konstantin Konstantinovich (1896–1968)

Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Shortly before the start of the war, in 1937, Rokossovsky was repressed, but in 1940, at the request of Marshal Timoshenko, he was released and reinstated in his former position as corps commander. In the first days of the Great Patriotic War, units under the command of Rokossovsky were one of the few that were able to provide worthy resistance to the advancing German troops. In the battle of Moscow, Rokossovsky’s army defended one of the most difficult directions, Volokolamsk.

Returning to duty after being seriously wounded in 1942, Rokossovsky took command of the Don Front, which completed the defeat of the Germans at Stalingrad.

On the eve of the Battle of Kursk, Rokossovsky, contrary to the position of most military leaders, managed to convince Stalin that it was better not to launch an offensive ourselves, but to provoke the enemy into active action. Having precisely determined the direction of the main attack of the Germans, Rokossovsky, just before their offensive, undertook a massive artillery barrage that bled the enemy’s strike forces dry.

His most famous achievement as a commander, included in the annals of military art, was the operation to liberate Belarus, codenamed “Bagration,” which virtually destroyed the German Army Group Center.

Shortly before the decisive offensive on Berlin, command of the 1st Belorussian Front, to Rokossovsky's disappointment, was transferred to Zhukov. He was also entrusted with commanding the troops of the 2nd Belorussian Front in East Prussia.

Rokossovsky had outstanding personal qualities and, of all Soviet military leaders, was the most popular in the army. After the war, Rokossovsky, a Pole by birth, headed the Polish Ministry of Defense for a long time, and then served as Deputy Minister of Defense of the USSR and Chief Military Inspector. The day before his death, he finished writing his memoirs, entitled A Soldier's Duty.

Konev Ivan Stepanovich (1897–1973)

Marshal of the Soviet Union.

In the fall of 1941, Konev was appointed commander of the Western Front. In this position he suffered one of the biggest failures of the beginning of the war. Konev failed to obtain permission to withdraw troops in time, and, as a result, about 600,000 Soviet soldiers and officers were surrounded near Bryansk and Yelnya. Zhukov saved the commander from the tribunal.

In 1943, troops of the Steppe (later 2nd Ukrainian) Front under the command of Konev liberated Belgorod, Kharkov, Poltava, Kremenchug and crossed the Dnieper. But most of all, Konev was glorified by the Korsun-Shevchen operation, as a result of which a large group of German troops was surrounded.

In 1944, already as commander of the 1st Ukrainian Front, Konev led the Lviv-Sandomierz operation in western Ukraine and southeastern Poland, which opened the way for a further offensive against Germany. The troops under the command of Konev distinguished themselves in the Vistula-Oder operation and in the battle for Berlin. During the latter, rivalry between Konev and Zhukov emerged - each wanted to occupy the German capital first. Tensions between the marshals remained until the end of their lives. In May 1945, Konev led the liquidation of the last major center of fascist resistance in Prague.

After the war, Konev was the commander-in-chief of the ground forces and the first commander of the combined forces of the Warsaw Pact countries, and commanded troops in Hungary during the events of 1956.

Vasilevsky Alexander Mikhailovich (1895–1977)

Marshal of the Soviet Union, Chief of the General Staff.

As Chief of the General Staff, which he held since 1942, Vasilevsky coordinated the actions of the Red Army fronts and participated in the development of all major operations of the Great Patriotic War. In particular, he played a key role in planning the operation to encircle German troops at Stalingrad.

At the end of the war, after the death of General Chernyakhovsky, Vasilevsky asked to be relieved of his post as Chief of the General Staff, took the place of the deceased and led the assault on Koenigsberg. In the summer of 1945, Vasilevsky was transferred to the Far East and commanded the defeat of the Kwatuna Army of Japan.

After the war, Vasilevsky headed the General Staff and then was the Minister of Defense of the USSR, but after Stalin’s death he went into the shadows and held lower positions.

Tolbukhin Fedor Ivanovich (1894–1949)

Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Before the start of the Great Patriotic War, Tolbukhin served as chief of staff of the Transcaucasian District, and with its beginning - of the Transcaucasian Front. Under his leadership, a surprise operation was developed to introduce Soviet troops into the northern part of Iran. Tolbukhin also developed the Kerch landing operation, which would result in the liberation of Crimea. However, after its successful start, our troops were unable to build on their success, suffered heavy losses, and Tolbukhin was removed from office.

Having distinguished himself as commander of the 57th Army in the Battle of Stalingrad, Tolbukhin was appointed commander of the Southern (later 4th Ukrainian) Front. Under his command, a significant part of Ukraine and the Crimean Peninsula were liberated. In 1944-45, when Tolbukhin already commanded the 3rd Ukrainian Front, he led troops during the liberation of Moldova, Romania, Yugoslavia, Hungary, and ended the war in Austria. The Iasi-Kishinev operation, planned by Tolbukhin and leading to the encirclement of a 200,000-strong group of German-Romanian troops, entered the annals of military art (sometimes it is called “Iasi-Kishinev Cannes”).

After the war, Tolbukhin commanded the Southern Group of Forces in Romania and Bulgaria, and then the Transcaucasian Military District.

Vatutin Nikolai Fedorovich (1901–1944)

Soviet army general.

In pre-war times, Vatutin served as Deputy Chief of the General Staff, and with the beginning of the Great Patriotic War he was sent to the North-Western Front. In the Novgorod area, under his leadership, several counterattacks were carried out, slowing down the advance of Manstein's tank corps.

In 1942, Vatutin, who then headed the Southwestern Front, commanded Operation Little Saturn, the purpose of which was to prevent German-Italian-Romanian troops from helping Paulus’ army encircled at Stalingrad.

In 1943, Vatutin headed the Voronezh (later 1st Ukrainian) Front. He played a very important role in the Battle of Kursk and the liberation of Kharkov and Belgorod. But Vatutin’s most famous military operation was the crossing of the Dnieper and the liberation of Kyiv and Zhitomir, and then Rivne. Together with Konev’s 2nd Ukrainian Front, Vatutin’s 1st Ukrainian Front also carried out the Korsun-Shevchenko operation.

At the end of February 1944, Vatutin’s car came under fire from Ukrainian nationalists, and a month and a half later the commander died from his wounds.

Great Britain

Montgomery Bernard Law (1887–1976)

British Field Marshal.

Before the outbreak of World War II, Montgomery was considered one of the bravest and most talented British military leaders, but his career advancement was hampered by his harsh, difficult character. Montgomery, himself distinguished by physical endurance, paid great attention to the daily hard training of the troops entrusted to him.

At the beginning of World War II, when the Germans defeated France, Montgomery's units covered the evacuation of Allied forces. In 1942, Montgomery became the commander of British troops in North Africa, and achieved a turning point in this part of the war, defeating the German-Italian group of troops in Egypt at the Battle of El Alamein. Its significance was summed up by Winston Churchill: “Before the Battle of Alamein we knew no victories. After it we didn’t know defeat.” For this battle, Montgomery received the title Viscount of Alamein. True, Montgomery’s opponent, German Field Marshal Rommel, said that, having such resources as the British military leader, he would have conquered the entire Middle East in a month.

After this, Montgomery was transferred to Europe, where he had to operate in close contact with the Americans. This was where his quarrelsome character took its toll: he came into conflict with the American commander Eisenhower, which had a bad effect on the interaction of troops and led to a number of relative military failures. Towards the end of the war, Montgomery successfully resisted the German counter-offensive in the Ardennes, and then carried out several military operations in Northern Europe.

After the war, Montgomery served as Chief of the British General Staff and subsequently as Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe.

Alexander Harold Rupert Leofric George (1891–1969)

British Field Marshal.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Alexander led the evacuation of British troops after the Germans captured France. Most of the personnel were taken out, but almost all the military equipment went to the enemy.

At the end of 1940, Alexander was assigned to Southeast Asia. He failed to defend Burma, but he managed to block the Japanese from entering India.

In 1943, Alexander was appointed Commander-in-Chief of Allied ground forces in North Africa. Under his leadership, a large German-Italian group in Tunisia was defeated, and this, by and large, ended the campaign in North Africa and opened the way to Italy. Alexander commanded the landing of Allied troops on Sicily, and then on the mainland. At the end of the war he served as Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean.